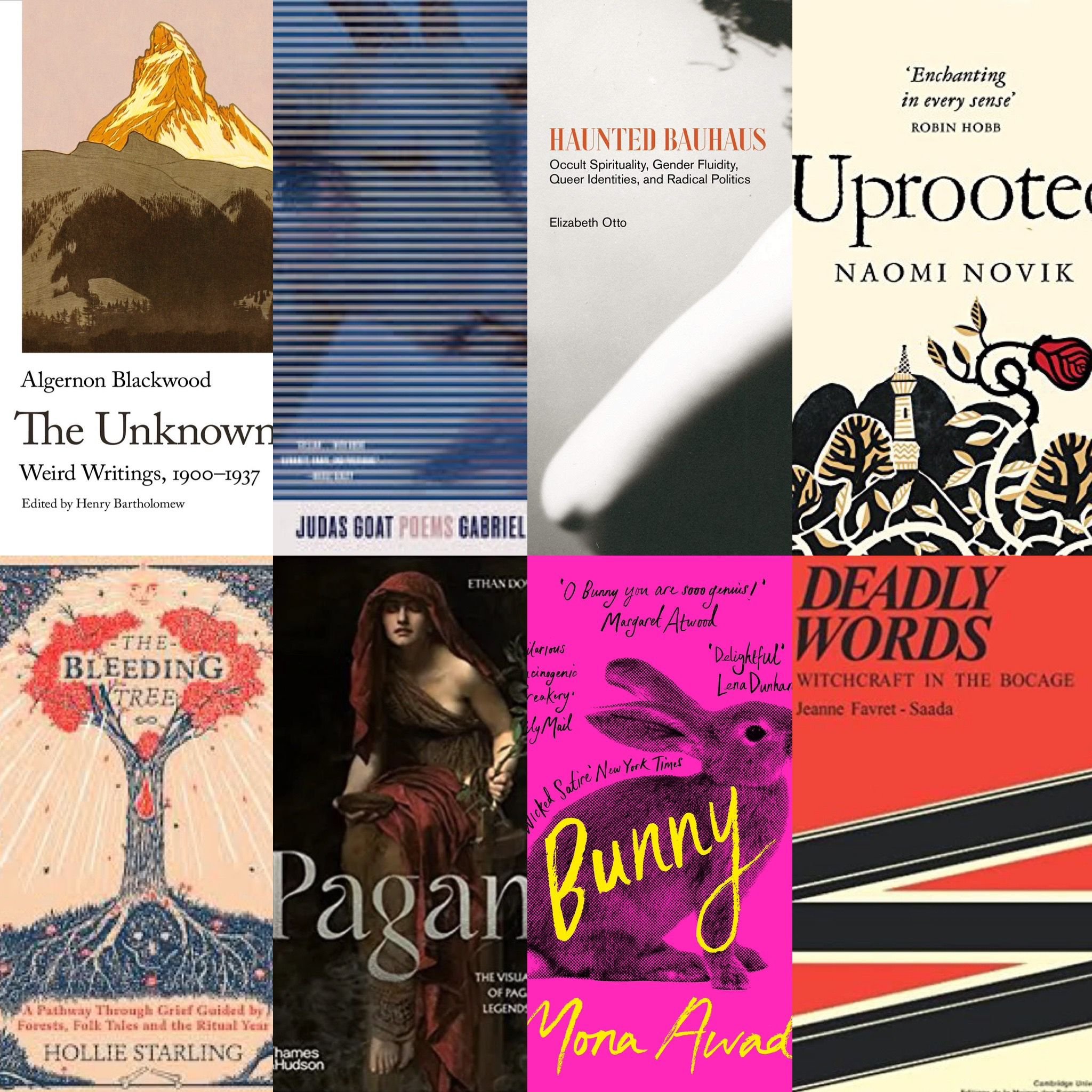

Bunny by Mona Awad – read by Dr Elizabeth Dearnley

I picked up this book after a tipoff from one of my students and absolutely devoured it. Set in an elite MFA programme ruled by a beautiful, pastel-clothed clique of girls who call each other “bunny’”, this hallucinogenic fairy tale of dark academia is laced with cupcakes, cocktails, human-animal hybrids, and some bloodthirstily unorthodox approaches to creative writing.

Deadly Words: Witchcraft in the Bocage by Jeanne Favret-Saada – read by Carl Holmes

This obscure, profoundly immersive, and genuinely disquieting book explores the often devastating consequences of what is said and, as importantly, unsaid in the context of a “peasant” witchcraft tradition in a remote region of France. Favret-Saada, a French anthropologist, was critical of orthodox academia's dry and distanced methodology, scorning the so-called neutral observer as a “non-combatant” in a “total war waged with words.” She came to believe that the only defensible approach for the resolute researcher was that which risked self-annihilation in surrender to witchcraft. This led to her becoming an “unwitcher” a magician at the service of those caught at the intersection of misfortune and “deadly words.” There is a real sense of lived experience in these pages, of secret things deliberately left unwritten.

The Book of Frank by CAConrad – read by Elizabeth Kim

Earlier this year, people crowded inside a warehouse in a Glaswegian suburb, warming their hands with paper cups of tea. They were all here to see CAConrad, a poet hailing from Kansas City, who described their childhood selling flowers on the roadside and later witnessing their friends die from AIDs in the 80s. CA wasn’t here to read from the somatic rituals for which they are best well known today, but from The Book of Frank, soon to be reissued by Penguin, but currently printed beautifully by Wave Books. I expected to hear an excerpt but we were treated to a reading of the entire book. This is a weird story in verse about Frank, a character who came to the poet and haunted them for more than a decade. CA’s verse is accessible and engaging. They blew bubbles to signal moving between parts and drew laughter from the audience on many occasions. Little wonder there was standing room only.. After reading, the poet described their belief that the poet is a vessel for poetry, a belief that goes back to the times of Homer. CA is a regular contributor to Cunning Folk and contributed to Spiritus Mundi; after the event, CA gifted me the reading copy of The Book of Frank – thank you!

The Bleeding Tree by Hollie Starling – read by Elizabeth Kim

Blending memoir, cultural analysis, and folklore, here is a personal tale about a subject often relegated to the realm of taboo: suicide. The author’s father’s suicide, to be exact. Uncannily similar in themes to the novel I’m working on, I have to be honest, when I received this proof in the post, I let it jump the line – setting aside the piles of ARCs waiting to be read. The connection between trees, folklore, and suicide is more subtle than I expected, but above all, I resonated with the author’s thoughtful meaning-making by examining her own lived experience and grief through the lens of folklore and the natural world. Suicide is taboo, but arguably this doesn’t help the thousands of people it impacts from grieving or accessing help. I would recommend it and have recommended it, to anyone going through something similar.

Pagans by Ethan Doyle White – read by Elizabeth Kim

Pagans are a tricky demographic to pin down. Today the term is used often to refer to Neo-Pagans, including Wiccans and Druids, whose new religions creatively draw inspiration from the past. The word “Pagan” has older roots, too, referring to various peoples, contemporary and historical, who worship(ped) not one god but many, from the Ancient Greeks to Hindus. Doyle White has done a good job of exploring the breadth of a slippery word that’s so often misconstrued. While dispelling myths, this is also a visual resource for many Modern Pagans, providing an accessible glimpse into the history, with references to various deities, shrines, symbols, festivals and more. The book is also illustrated by beautiful photographs and paintings, and produced to high standards, as we’ve come to expect from Thames & Hudson. We’re lucky to be running a giveaway on this title in April. Keep an eye on our socials for a chance to snag a copy!

Too Hot to Sleep by Elspeth Wilson – read by Elizabeth Kim

Bedridden for a few months now, I have really enjoyed dipping in and out of poetry collections. Too Hot to Sleep is Elspeth Wilson’s debut pamphlet, and proved short and engaging enough to read in one sitting. Described as a book that “explores the way we inhabit our bodies from the perspective of a queer, disabled, neurodivergent artist”, it felt apt reading for me right now. Wilson’s poetry is very much a vibe. The tight and spare poems are nostalgic and harken back to an easier time: 90s sleepovers, supernatural pop culture including vampires and witches, all set against the bleak backdrop of the ongoing climate crisis, with wildfires ripping across countries. Come along to the launch at Lighthouse Books in Edinburgh on 11th May.

Uprooted by Naomi Novik – read by Dr. Elizabeth Dearnley

I can never resist a forest-set fairy tale (especially if Baba Yaga is involved), and Uprooted charts a bewitching path through the woods from start to finish. Telling the story of Agnieszka, who is taken from her village to serve a formidable dark wizard known as the Dragon, this spirited take on Beauty and the Beast weaves together Polish folklore, gorgeously tactile spells made from rosemary and lemon, a determinedly resourceful heroine, and trees with minds of their own.

Her Body and Other Parties by Carmen Maria Machado – read by Cristina Ferrandez

Carmen Maria Machado’s memoir In The Dream House was one of the most talked about books of 2019 with its deconstruction of genre and exploration of abuse in queer relationships. But before In The Dream House, Machado published Her Body and Other Parties, a groundbreaking collection of feminist short fiction. The collection includes stories ranging from ‘Especially Heinous’, a reimagining of every episode of Law and Order: SVU which grows gradually more and more absurd, to ‘Real Women Have Bodies’, in which a strange plague makes women slowly fade away until their flesh is barely visible. The most striking story, in my opinion, is “The Husband Stitch”, a collage of urban legends and some of the horror stories that have kept generations of us awake at night, all retold in an attempt to make sense of the relationship dynamics between a woman and her husband. Machado subverts these stories to explore contemporary gender issues such as female desire, toxic masculinity, and consent. The effect is visceral and revelatory and the short story remains one of my all-time favourites.

The Witch Doll by Helen Morgan – read by Dr. Elizabeth Dearnley

This shivery children’s book about two girls who find a small wooden doll – and make the unwise decision to fit it with the blonde wig of hair found next to it – terrified me as a child. Returning to it recently while researching doubles and doppelgängers, I found Morgan’s story (and the book’s horrifying half-doll, half-human cover design) to be just as chilling as I remembered.

Haunted Bauhaus by Elizabeth Otto – read by Carl Holmes

The Bauhaus school of art and design is often synonymous with modernism and “male” gendered abstract rationalism: a minimalist aesthetic of hard edges and pared-down functionality. In the wittily titled Haunted Bauhaus, Elizabeth Otto “queers” this view by highlighting the fluid, irrational and anti-utilitarian approaches taken by the more bohemian members of the school, whose receptivity to occult spiritualities and radical currents in politics and philosophy found expression in lifestyles that actively sought to subvert gender, sexuality, and identity norms. Standard narratives tend to ignore or gloss over the ghosts that trouble the Bauhaus brand, binding and banishing them to the margins; with Haunted Bauhaus, Otto performs a timely resurrection.

Judas Goat, Poems by Gabrielle Bates – read by Beth Ward

This debut collection of poems by Gabrielle Bates is about intimacy. It's about place, the way it haunts us and makes us. It's about bodies and obedience. It is about mothers and daughters. Touch, death – each of its poems glimmering with a kind of harshness, an incisiveness, Bates' verses like knife blades against soft petals.

In the collection's opening poem, "The Dog," Bates gives us lines so clear and evocative as to be nearly tactile.

"When we went to bed, I stared at the back of his head

split between compassion and fury. My nails

gently scratching up his arm, up and down, up and down,

the blade without which the guillotine is nothing."

These from "When Her Second Horn, the Only Horn She Has Left," are so tender and taut that the reader can nearly feel the line breaks against her own wrist.

"When her second

horn, the only horn she has left,

goes up through the white and copper-topped

tunnel of my eye and enters the basket of bone,

we are no chimera the ancients ever dreamed."

Judas Goat's poems are brutal and beautiful. They're the kind of poems that your body reads, that resonate somatically, that are felt before they're learned. Bates took me somewhere in these poems that I still haven't come back from.

The Unknown: Weird Writings, 1900-1937 by Algernon Blackwood – read by Elizabeth Kim

Algernon Blackwood is a writer more of us should know about, suggests Henry Bartholomew, the editor of this short story collection. A contemporary to Arthur Machen and WB Yeats, Blackwood was one of the foremost British writers of horror and ghost stories, and his early work was admired by young writers including H P Lovecraft, C S Lewis, and JRR Tolkien. Blackwood drew creative inspiration from his love for mountain climbing and skiing, while his more metaphysical leanings borrow heavily from his interest in Buddhism and the occult. A founding member of Toronto’s Theosophical Society, the author was also a member of the Ghost Club, and the Hermetic Order of the Golden Dawn. The twelve stories and essays in this collection are full of dread and wonder, hinting at the immensity of the unknown forces that lie beyond what we think we know. I am still reading this, slowly, but one of the most representative and well-known stories in the collection is “The Glamour of the Snow”; eerily it begins with a line that promises nothing is quite as it seems: “Hibbert, always conscious of two worlds, was in this mountain village conscious of three.”