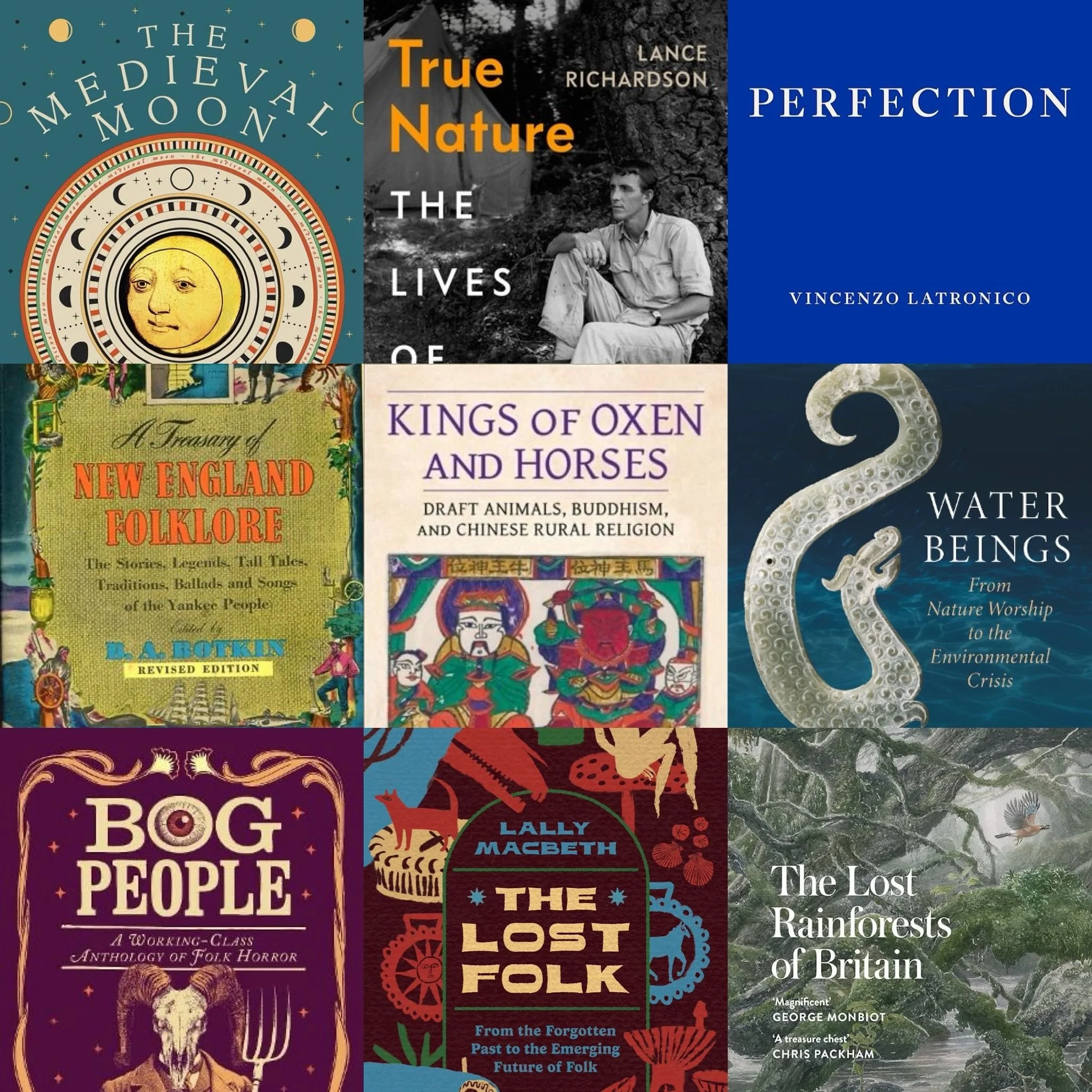

We have accidentally been on hiatus – but we’re slowly resurrecting. Here’s what we've been reading of late.

Pixie by Jill Dawson (2025)

Pamela Colman Smith – affectionately known as ‘Pixie’ – was a fascinating figure. Well-travelled, a member of a London secret society, she is best known as the illustrator behind the Rider-Waite-Smith Tarot deck so many readers use today. Generous with exclamation marks in her letters, Smith could so easily be reduced to the Manic Pixie archetype, but she is clearly a more complex person, questing for something deeper; Jill Dawson captures her multifaceted character well: ‘And other times, a voice comes to me in my head, just like my speaking one, and says: It’s you one day. You will die too — isn’t that the secret that no one believes — no one wants to know?’ From Jamaica, to New York, and then to London, with Pamela we enter into the world of the Hermetic Order of the Golden Dawn and meet her well-known peers, following their searching. Filmmakers: here is a book begging for adaptation – what a biopic it could be.

The Lost Rainforests of Britain by Guy Shrubsole (2022)

Barren fields, sheep, pastoral postcards; we think of the British landscape as one thing, when once it was very different — a realm of enchanting mists, mossy forests, curling ferns, lichens and liverworts. Guy Shrubsole makes a good case for protecting our last temperate rainforests, culturally and ecologically vital to this land, integral to the magical tales within this island’s most important stories, including the Mabinogion. Shrubsole speaks with activists, lecturers, farmers, advocates for rewilding, and illustrator Alan Lee, among others. Of the people of Wales’ past who lived with Atlantic Oakwood’s, Shrubsole writes ‘They knew these rainforests and knew them deeply, weaving them into their stories, vesting their greatest heroes with a magic derived from that profound knowledge of place and ecology’

Water beings by Veronica Strang (2023)

Water is essential and destructive; life-giving and life-taking. People have worshipped it and feared it, for what is capable of, all it represents, and for the monsters – or spirits – who dwell beneath the surface. From giant anacondas to rainbow-bringing snakes, from dragons to horned serpents. Veronica Strang offers a comprehensive compendium of magical water entities rooted in respect towards our shared rivers, lakes and oceans.

The Lost Folk by Lally Macbeth (2025)

An accessible and thoughtful introduction to Britain’s folk collectors. Lally Macbeth reminds us that folklore is for everyone, and rather hard to pin down or standardise. This offers a refreshing parallel history to the more canonical art history, reappraising the folk art and customs of common people. What we find is a body of material culture less concerned with ego and legacy and more concerned with life, beauty and nostalgia.

Bog people edited by Hollie Starling (2025)

After reading Hollie Starling’s poignant memoir The Bleeding Tree, we were looking forward to this one. ‘When a person’s chances in life are sealed by an accident of birth it’s no coincidence that it is the pitchfork that has become the most familiar totem of the angry mob,’ writes Hollie Starling in her erudite introduction. This compelling anthology of folk horror comes from working glass voices including AK Blakemore, Emma Glass and Salena Godden. Expect more from us on this title in autumn – it’s our next Cunning Folk Book Club pick.

Kings of Oxen and Horses by Meir Shahar (2025)

It was a taboo to eat beef in China’s past, possibly a feature of native religions, or in Meir Shahar’s view, imported from India. Dare eat an ox and farmers worried they could upset the Oxen King who would seek vengeance; beef-eaters could be reincarnated as a cow and devoured in turn. A deeply researched overview of beast of burden tutelary spirits of Song Dynasty China certain to make us reckon with our choices today.

A Treasury of New England Folklore by BA Botkin (1947)

We chanced upon this old tome while visiting New England last autumn and were delighted to find such a readable and comprehensive introduction to the region’s stories, ballads, rhymes and folk customs, from renowned American folklorist Benjamin A. Botkin. Expect nostalgic, curious miscellany, ghost stories and local legends, interrupted, at times, with sheet music and character portraits.

Legends and Lattes by Travis Baldree (2022)

We found this in George RR Martin’s Santa Fe bookshop, Beastly Books, and wanted to see what low stakes fantasy was all about. An orc retires from adventure and sets up a coffee shop. What follows is a somewhat ponderous but cosy account of high fantasy characters sniffing coffee beans, setting up shop, and enjoying their brew with pastries. It moves at a snail’s pace, and very little happens beyond cosy fantasy vibes, but it’s obviously emblematic of a moment, a desire for an escapism that doesn’t feel too stressful. It is above all kind.

Perfection by Vicenzo Latronico (2022)

‘If they asked around, talked to some newsagents and oldies in the local bars, they might just find somewhere with a difference – one that hadn’t yet been spoiled by the internet.’ This near-perfect novel does not, on first glance, contend with our themes, though many readers will likely resonate with its portrait of disenchanted times; within we find the relatable problems associated with the internet and late stage capitalism. Perfection was shortlisted for the The Booker Prize this year and, for a quiet novel, has proven an unexpected bestseller.

Saint of by Lisa Marie Basile (2025)

Lisa Marie Basile is an extraordinary writer of gilded prose and verse. Her writing aches with intense feeling and beauty. This is such a brilliant idea for a poetry collection, one that feels bold and very rooted in place. In the word of her publisher: ‘These poems are not only an invocation of saints,—they are a declaration of self.’ In Marie Basile’s own words, ‘What girl can know the abyss / without becoming it?’

True nature by Lance Richardson (2025)

Peter Matthiessen was the co-founder of the Paris Review and author of books including The Snow Leopard and Shadow Country. He wandered the Himalayas in search of the snow leopard, practised Zen Buddhism and became quite obsessed with Big Foot as a “productive symbol”, as his biographer Lance Richardson puts it. Deeply researched and engaging, this is a rather long book at around 700 pages, but I enjoyed this biography more, perhaps, than Matthiessen’s work.

The Medieval Moon by Ayoush Lazikani (2025)

A fascinating look at earth’s satellite, how it has inspired writers and artists, its associations with romance, madness, the human body and transformation. This offers a cross-cultural look at myths and folk stories about the moon, from proto-science fiction True Story by Lucian of Samosata (160 CE) to the man in the moon. Oxford lecturer Ayoush Lazikani’s telling is authoritative but open to myriad tales of the moon’s magic and mystery. The moon is also a potent symbol for prophecy: ‘In a tale from the 700s, a pregnant woman has a vision: a waxing moon is before her. The moon grows and grows, and when it reaches the size of a full moon, it tumbles through her lips and her chest becomes aglow with light. This is the mother of Willibrord, a man who will become a saint …’