Elizabeth Sulis Kim Your book is named after a Kate Bush song. Can you explain that?

Pam Grossman It’s definitely winking at the Kate Bush song. I love her. I love her music. I love that song. But she and I are also referencing a pretty horrific means of torture that was used during the time of the European witch hunts, which was sleep deprivation. In order to get a so-called witch to confess, you would not allow her to sleep. You’d wake her up in the middle of the night and try to get her to confess when she was more vulnerable, when her defences were down. So there is that kind of dark background to it as well. I love that idea of re-appropriating this terrible practice and transforming it into a kind of call to arms and celebration. I loved even the phrase being re-appropriated into this positive phrase, a phrase that will hopefully galvanise people and allow them to feel inspired by this archetype in the way I am.

ESK Why were you drawn to witchcraft as a child?

PG Oh my goodness. I often say “baby I was born this way.” I just loved books and television shows and film and artwork that centred on magical females. Sometimes those were witches. One of my favourite novels growing up was Wise Child by Monica Furlong, which I mentioned in the intro to this book, and that was a very powerful, very witchy book. But honestly I loved mermaids, I loved fairies, I loved anything that had to do with the magical feminine. I was just a very imaginative kid. My love of creativity in all forms, whether that was drawing or doing spells in my backyard or writing stories, all kind of developed at the same time. I really see my creativity and my magic as two sides of the same coin.

ESK How did your parents take you becoming a witch?

PG I started publicly calling myself a witch as an adult, over 10 years ago. But privately thinking of myself as a witch—or some kind of magical girl— since I was very small. And my parents were honestly very encouraging. They’re Jewish and I was raised Jewish. But both of my parents are artists. My dad is a musician and my mother is a painter. They’ve had many different day jobs but art was a big part of my upbringing. My mum is very into the divine feminine and goddesses and my dad is very into meditating and Buddhism. So I was very fortunate to be raised in this eclectic and open-minded and creative household. My parents just wanted me to be myself.

ESK In Waking the Witch, your perspective seems consistent with Ronald Hutton’s view of witchcraft being a very creative, non-dogmatic path, set of beliefs or a new religion. You talk a lot in your book about how witchcraft is not a set of dogmas but something personal. You also write about your initial discomfort at participating in group work and joining covens. When people come together in a group, how do you avoid groupthink and how do you avoid creating dogmas?

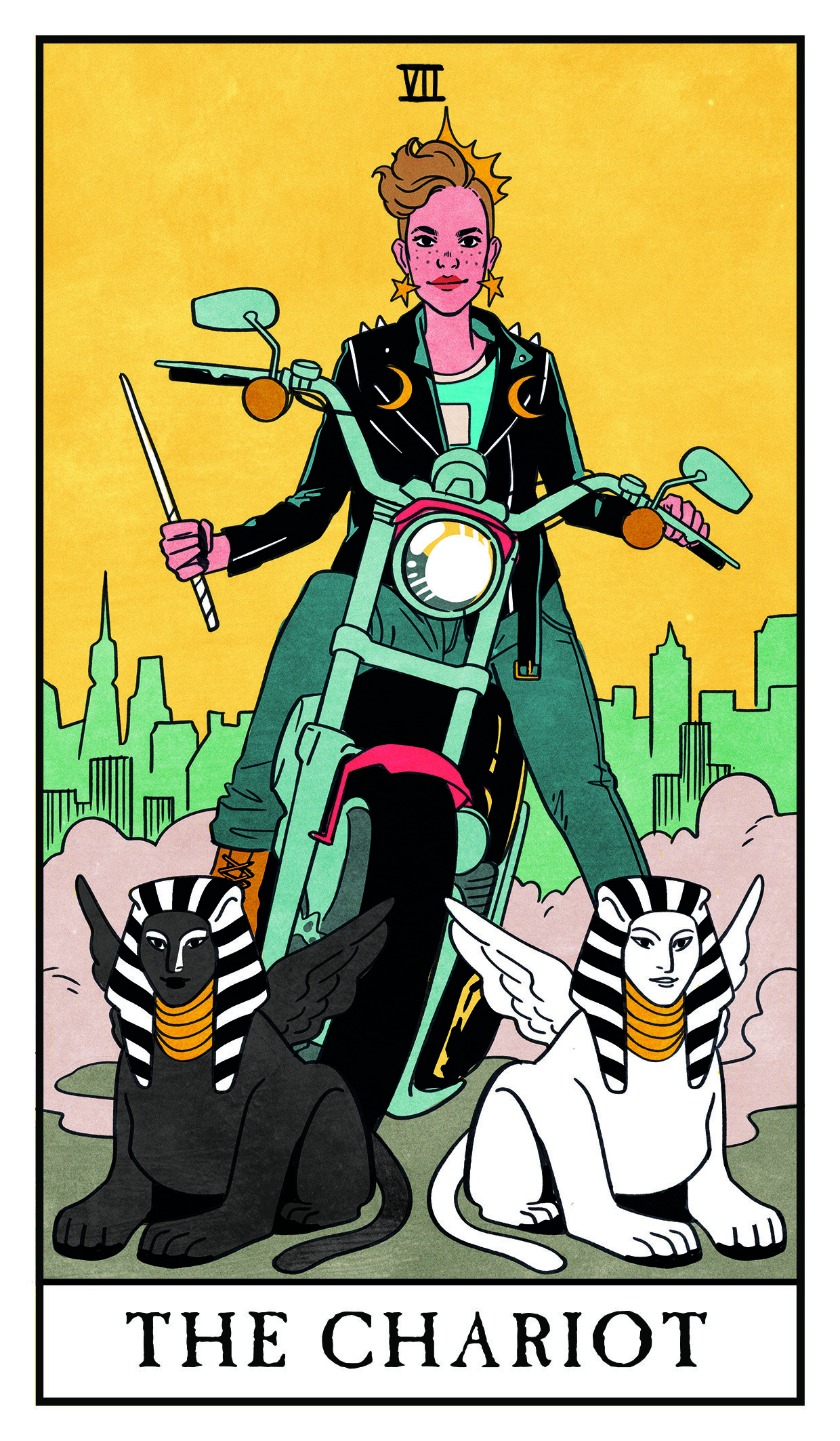

PG I think one of the great things about witchcraft is there is no one leader. That can also be challenging at times, but because there is no one leader, because there is no one book, one set of dogma, no pope or one high priestess or authority figure the way there is in some other religions, that really allows for free thinking and evolution. That also means there is debate and there are some different perspectives and interpretations when it comes to what magic is and what a witch is and how a coven should operate. I can only speak to my own experience, but generally speaking, it has been hugely positive for me to find groups of kindred spirits who are fortifying each other and supporting each other and connecting with each other. While the image of the solitary witch is certainly part of the archetype, and I was a solitary witch for most of my life, we need each other as human beings. We can’t change the world by ourselves. So I think for whatever shortcomings groups may have, they are ultimately the way forward as they are a way of pulling our resources and sustaining each other, and we need that if we are going to make the changes that need to be made in the world. That doesn’t mean everyone needs to join a coven. For some people, their solitary work is hopefully fortifying them enough so they can go do whatever work they need to during their everyday lives. But I do think that unity and interconnection while still respecting each others’ individual perspectives is the way that we’re going to fix the broken parts of this world.

ESK People are increasingly interested in magic and witchcraft, feel in many ways an existential need for it, but often struggle to actually get on board with the belief in magic, deities and the rituals. How can you reconcile the two?

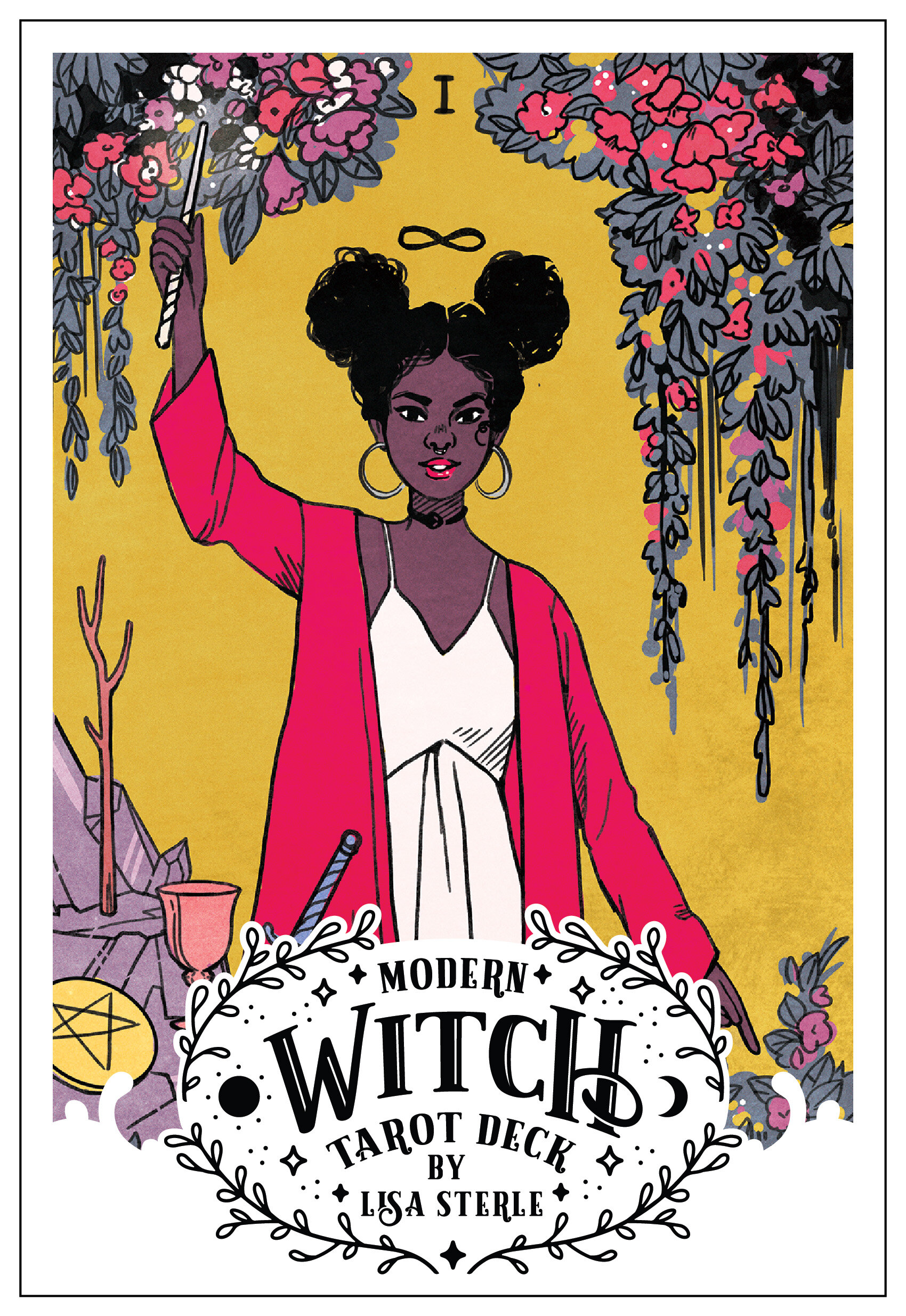

PG This is really one of the thesis statements of the book. The term ‘witch’ means so many different things depending on the context. We’re taking a word that has traditionally been used as a negative epithet against people, particularly women, for many hundreds if not thousands of years, obviously in different languages too. To me, I think the most useful way of thinking about the witch is as a symbol or an archetype, and so nobody owns that word. I know some Wiccans or some modern Pagans or some people have what they identify as a witchcraft practice in their own family lineage, may feel ownership of that word, and I can see why. But at the same time, it is a word that has been fairly recently re-appropriated as a positive thing to be, because it was such a negative word that has been used to brutalise people. For me, if someone calls themselves a witch, it is an act of reclamation. That can be for spiritual purposes for sure. But it can also be for political or cultural purposes, so if someone calls themselves a witch because they are a feminist or an environmentalist or they see themselves as someone who is subverting white cis straight heteronormative forces, I’m all for it. If that’s a word that gives them a sense of empowerment and allows them to tap into their own purpose and meaning-making and change making, then I think that’s a wonderful thing.

ESK So there’s been a boom in witchcraft in the past few years. You wrote about how the witch archetype is often something people who are somehow marginalised or feel like an outsider identify with. You also wrote about the re-appropriation of the term witch hunt, often by middle-class white men in power. Do you think the witch can ever be re-appropriated by people aren’t somehow deemed ‘other’ by society?

PM I really grapple with this question a lot. To be honest, I don’t have a clear answer to it. But I think we’re talking about a few different things at the same time and I think it’s important we tease this out a little bit. With my own biases and and my own opinions about what the word means to me, I do think it has come to symbolise someone who carries a spirit of rebelliousness and transformation and defending the most vulnerable, someone who is a feminist, someone who believes in the powers of imagination and intuition to make literal, material change in their lives and in the world, so it has that very specific meaning to me and many other people. But I can’t stop anyone from identifying with that word. And it is a really curious, shapeshifting word that has so much nuance and so many facets, so people are going to continue interpreting it and giving it many new meanings for many years to come. Ultimately it’s a word which no one has ownership over, and ultimately there’s no gatekeeper for that word, including me.

The question: can white people who call themselves Wiccan or witches—but are doing so by appropriating certain cultures that are not white—is that a problem? Absolutely it’s a problem, and I talk about that towards the end of Waking the Witch. There’s a question in society in general about appropriation and being respectful to cultures other than one's own—people’s backgrounds other than one’s own, acknowledging your behaviour and being responsible. Essentially I think that is its own issue. So when it comes to magical practice, certainly there are certain practices that originate from the African diaspora, from indigenous cultures, certainly in America but also all over the world. That can be very problematic and offensive and exploitative. A really good example is the popularity of so-called “smudging”, which certainly in the US has an offensive association with Native American people. To them, even that word is a word that belongs to their culture, a ritual that belongs to their culture. It doesn’t mean you can’t burn herbs to protect yourself—but to use the word without getting permission to use it or knowing what that word means—or what those rituals are— is very offensive. Can anyone just call themselves a witch? Can a chick who’s just really into crystals who has just got into them a month ago call herself a witch, compared to someone who might have been studying witchcraft for most of their lives, or who have gone through certain initiations, or who has done tonnes of research about it? I think it’s that kind of conversation that I think is honestly a bit of a waste of time. People are attracted to explore the archetype of the witch at many different times of their lives. Who am I to judge someone who is just very enthusiastic and new to this community or this word—who might not have the same experience I do. Also our idea of who is oppressed: who am I to judge? Obviously, you need to know your privilege, I think especially here in the states, people of colour, women, non-binary people and trans people definitely do not have the same rights as cis white men. So I think that’s why the archetype of the witch is so attractive to people of colour and gender non-binary people and trans people and queer people, because the witch is so often an outsider.

ESK Thank you for such a thorough answer. Quite timely, you wrote about the threats to bodily autonomy in the US in your book—and obviously, things have got worse since. Generally, do you think people turn to magic when they feel politically disenfranchised?

PG I think that’s absolutely part of it. One issue I have with that though is that magic never goes away. There are always people who are practising it, studying it, attracted to it, using it in their own creative expression, but in terms of why it seems to get more popular, or at least the media seems to focus on it more, it is certainly a means of tapping into one’s power, particularly when our governments, our businesses, our religious organisations are oppressive and harmful, which we’re seeing all over the place. So I do believe that magic is a really great alternative system for world-building. If you look at the four waves of feminism, at each crest of those waves you see a renewed interest in the witch, and you see the witch being taken up as this symbol of feminine, rebellious power. Autonomy over bodies that are not up to the “standard” of whoever is in power and whoever is making the rules. In terms of a pattern, absolutely, but I always want to be careful because I don’t think it’s as simple as witches being a trend. I actually see it as more a growth in interest in this archetype that’s gaining momentum over time and has been since the 19th century when women and people of colour were starting to demand rights and to tap into their own sense of worthiness, particularly here in America.

ESK Speaking of “tapping into one’s power,” you’ve said that for you magic is synonymous with art. Can you just expand on that? I mean, what is magic for you personally? I think that’s something I’ve struggled with myself.

PG I think the word magic is like the word witch in that it means so many things, and it depends on the context and it depends on who is using it. When I’m talking about magic, I’m talking about an invisible force that is catalysed by the imagination and ritual to make consciousness shifting change, which can often result in material change in the real world. I know in my own experience that my own focus and attention and intention are all important tools in my own magic-making and that my spells and my creative work are all more effective when I’m focusing my imagination, attention and intention on the work. In other words, every time somebody draws a picture— is that magic? I’m not entirely sure. I think there’s a relationship there and when it is infused with intention then it can be a magical act.

ESK Why do you think people are still scared of magic?

PG Because there have been thousands of years of propaganda against it. I think people fear the unknown— they always have. Certainly, we saw in the middle ages and early modern period, a very targeted campaign not just against witches, but against magic and the occult in general by the Church. There started to be an influx of translations of occult books from other cultures that the Church deemed very threatening. As I write in the book, the devil wasn’t even that big a concern to the Church. The devil is barely mentioned in the bible, and really it was when these books started getting translated in the middle ages. So really it was in the middle ages that the Church started feeling very threatened by all these occult books that started being translated and these outside forces, and that’s when the devil as a character played a much bigger role in Christian rhetoric. Shortly after that the witch quite literally became his bedfellow in stories and in writings about diabolism, which was seen as a very real threat to people but certainly to the Church overall.

ESK And what about with the conflict between science and magic. I think science in a way has the same goals as the occult—to explore the unknown and to discover new things. Do you think that the same sort of discourse that’s anti-witchcraft and anti-magic continues in the so-called “rational” age?

PG I certainly think so, particularly in academia there’s still a lot of disdain for magic. It’s seen as the opposite of so-called rationality and objectivism and empiricism. So some people think that, but what’s interesting is if you think about someone like Isaac Newton, he was very into alchemy and mysticism, and now with studies of Quantum Physics and all these amazing things that are showing that in fact, our thoughts can affect the material world in literal ways, I think those lines between science and magic are starting to blur once again the way they did pre-enlightenment, because magic and science were kind of considered part of the same spectrum. So I think we are starting to circle back. There are so many people now who are starting to get interested in things like spirituality and psychedelics and meditation, all of this stuff that was often seen in the more mystical realm, and people are starting to realise that there is some kind of science to it, that there is an actual physical effect to these different practices. So I think we’re starting to circle back to a time when spirituality and science are seen as having this very deep relationship that is real and that one doesn’t necessarily have to discount the other.

ESK Definitely. We’ve come to think in very categorical terms, particularly in Western society. Many of the artists, musicians, writers and some scientists I know were in some way influenced by the occult. So do you think history is cyclical?

PG I don’t know. In a lot of witchcraft conversations we have, we tend to use the image of the spiral - particularly one that spirals upwards, picture yourself climbing a mountain or up a spiral staircase. It’s this notion that things are improving and we are elevating our consciousness together, but when you do that you keep having to loop backwards. It sometimes feels like you’re having to retrace your steps, and it sometimes feels like you’re not learning from history, but in fact, you have to revisit some of the dark shadowy things in order to move forwards and upwards. So that’s the image that resonates the most for me, and it’s one I really hang onto, especially in tough times. I know you’re going through difficult times with your government, here in the US it really does feel like we’re going backwards. I just have to hang onto the notion that we’re doing that in order to really look at our shadows and our monsters and hopefully figure out ways to move through them so they don’t have to keep coming back to us, and that we’re getting to be more sensitive, kinder and more compassionate people. People who care about the earth. People who care about the most vulnerable. People who care about each other.

ESK That’s a really hopeful perspective.

PG Yes, for me the witch is hopeful in that way. You can’t talk about the witch without talking about a history of horrors against women and against outsiders, and the fact that the witch has been re-signified as this beacon of hope, and that we have shape-shifted her and re-made her, and she shape-shifted and re-made us in turn, is something I see as extremely hopeful. That’s one of the biggest takeaways I hope people get from my book. Even though there’s a lot of pain and suffering and oppression, that is inherently part of this archetype, it is ultimately a liberating force that I think can shine some light and illuminate our path forward.

ESK Yes, I got that from reading your book. I saw you also started the Occult Humanities Conference at New York University, despite the aforementioned general academic disdain towards the occult. How did that come about and how have other scholars taken it?

PG Interestingly we are seeing more and more classes and academic degrees that are including studies of esotericism and witchcraft and the occult. It’s happening in the states and some areas throughout Europe, including England. I would say it’s been in the past 10-15 years and it now seems to be gaining steam and validity. Remember, just because you have a conference doesn’t mean you have to believe in it. You and I know a lot of the people who are attracted to this material also have some kind of spiritual practice. But there are those who don’t and it’s still important that we study the history of these concepts and practices. So I’m really excited by the fact academia is starting to embrace these different paths of scholarship. And obviously, they should because the occult has been hugely influential on so many people throughout history who have shaped our culture. If you look at art history alone, the whole advent of the modern art movement has spiritual roots, and roots in theosophy and spiritualism and ceremonial magic and all of these things. Just because it might make some scholars uncomfortable doesn’t mean it’s not a very key part of the lineage of thought in our culture.

It gives me a lot of hope because there are so many indigenous cultures that have shamanism and ritual and consciousness-altering plants as part of their healing practices, and I think for a long time there has been the notion that these cultures were “primitive” and now scientists are starting to realise that those people got it right all along, that they weren’t just making things up because they were ignorant, but actually they were tapping into some deep wisdom. It will only benefit us if we honour those practices in respectful ways and learn from them. We’re seeing it in the environmental movement, certainly in the medical sphere. I was just listening to a podcast this morning with Michael Pollan, the writer who famously has written about food and agriculture for many years, his most recent book How to Change your Mind, is about psychedelics, how they can heal depression and anxiety and PTSD. This is using the plants of the natural world that many shamans have been using for many thousands of years. I’m excited by the notion of science and magic and spirituality all learning from each other.